It started with a promise to practice taking up space—because our shrinking never serves anyone.

Feminist Lent might seem odd. Getting bigger for Lent isn’t the norm. But here’s the thing: Lent is about humility. And for women, humility probably doesn’t mean becoming less.

It probably means taking the risk of showing up with all of ourselves—when standing down gets you safety, comfort, acceptance and the crumbs of privilege for following unspoken rules.

It probably means doing something scared.

It probably means refusing to hide anymore.

And here’s the thing about feminism: it’s not just about grabbing Girl Power for yourself. It’s about living into a world where everyone is free.

It’s about paying attention to how power operates in every sphere of life, and choosing to be led—not just by women—but by women on the margins: Black women. Indigenous women. Single women. Older women. Fat women. Trans women.

All of those are things many of us need extra prayer, encouragement, and care to do. They are ways we need God to remind us who we are as we are practicing them. They are courageous actions of breaking free from old habits that need to die little deaths before we celebrate the resurrection.

Jesus chose the margins. Jesus chose a physical body. Jesus chose rest. Jesus chose to upend expectations.

That’s why Feminist Lent.

If you want to join me, just sign up below! You’ll get a note from me (about like this one, or shorter) about one of the six practices above most days during Lent.

Then share this post with a feminist friend!

I can’t wait to spend this beautiful season learning and loving with you.

peace, love, bread, and wine,

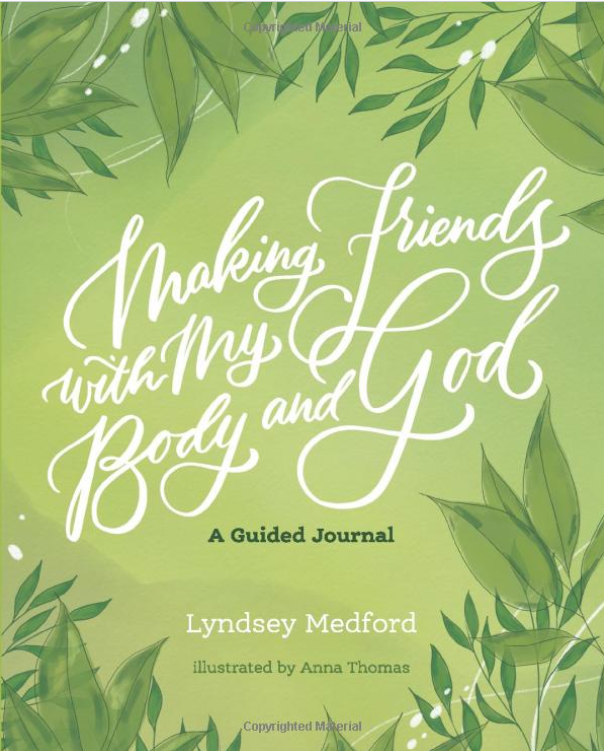

Lyndsey